Uncertainty and Misinformation: What to Expect on Election Night and Days After

Authors: Kate Starbird (UW), Michael Caulfield (WSU), Renee DiResta (Stanford), Jevin West (UW), Emma Spiro (UW), Nicole Buckley (UW), Rachel Moran (UW), Morgan Wack (UW)

UW: University of Washington, Center for an Informed Public

WSU: Washington State University

Stanford: Stanford University, Internet Observatory

Main Take-Aways

Democracy depends on trust in elections; that trust is under attack — both accidental and intentional. This will continue on Election Day and the days/weeks following.

The winner of many federal, state, and local elections will likely not be known on Election Day due to an increase in mail-in voting.

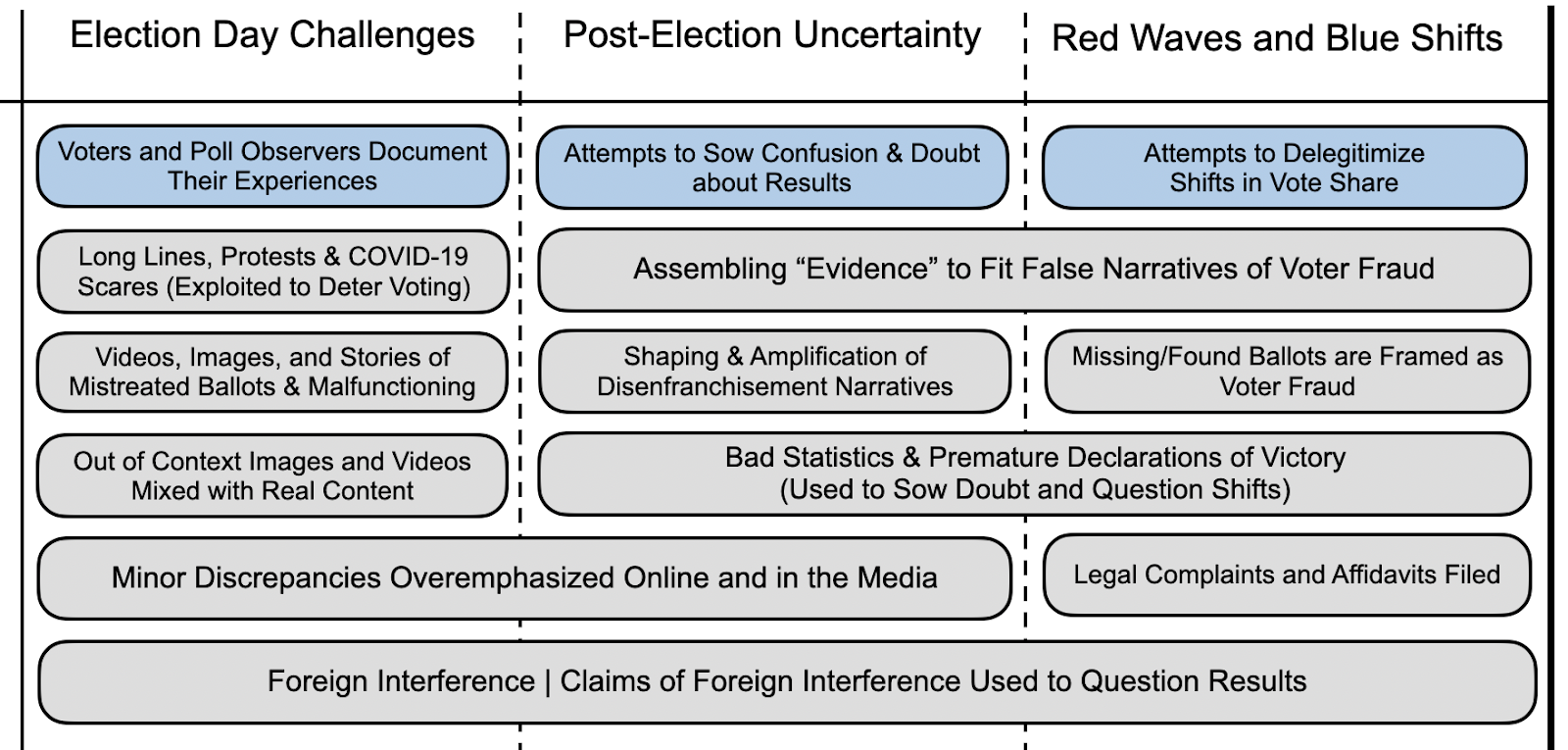

Uncertainty, anxiety, and potential red/blue or blue/red shifts will create opportunities for domestic and foreign political actors, conspiracy theorists, and other opportunists to delegitimize the election results.

There will be efforts to deter voting with images and videos of long lines, COVID-19 dangers, and protests.

The voting process (successes and failures) will be intensely documented, but the problems will be strategically framed and overemphasized to fit misleading narratives.

On the night of the election (and in the uncertain days that follow), premature winners will be declared, disenfranchisement will be highlighted, and “evidence” will be assembled to support false narratives of voter fraud. When they take action to address election-related misinformation, social media companies will be accused of censorship.

To support narratives seeking to delegitimize a shift in vote share from one party to another, lost and/or found post-election ballots will be problematized and politicized, affidavits will be filed, allegations of foreign interference will be made, and “bad statistics” will be selectively highlighted.

Advice to journalists and the public: prepare for uncertainty of results on election day/night, emphasize the vast majority of ballots and polling stations will experience no issues, highlight positive experiences of voting, know the conspiracies around shifts in vote shares, look to statements from election officials, and avoid sharing premature results from candidates or armchair data scientists.

Introduction: From Rapid Analysis to Prediction

The U.S. general election, less than two weeks away, is unprecedented in several ways. We are currently in the midst of a devastating pandemic, with infection numbers hitting rising across much of the country. In response to the pandemic, election officials in some states have adapted and modified their voting processes. Many are relying upon mail-in ballots in new ways and at new scales. Even states with universal mail-in balloting are seeing new challenges such as increased turn-out. This has created opportunities for some to question, and diminish trust in, the election processes. We have heard repeated (and mostly unfounded) accusations, sometimes from the U.S. president himself, that mail-in voting will lead to widespread fraud and that the election is “rigged.” Researchers have described this as an elite-driven disinformation campaign and though this campaign is largely shaped by right-wing media and political influencers, its effects aren’t limited to one side of the political spectrum.

Regardless of origins or intent, these attacks on the perceived integrity of the 2020 election represent a threat to democracy itself. If we are not able to trust and accept the outcomes of our democratic processes — e.g., the vote — then our democracy itself is at risk.

Over the last few months, our team has been conducting rapid analysis on various information events that threaten election integrity — for example, calls to action that might lead to voter suppression and incidents where discarded mail and/or ballots are framed in misleading ways to undermine trust in mail-in voting. Often in our work, we are looking backwards and playing catch up, trying to quickly debunk and then slow or stop the spread of false narratives. In this article, we look forward, applying what we have learned from our previous analyses to anticipate what might come next. Our hope is by doing this, we can prepare journalists and the broader public with tools to help reduce the impact of election-related mis- and disinformation and preemptively dampen its spread.

Drawing on our rapid-response research on election integrity, we present scenarios outlining what to expect in our information spaces on election day and the tumultuous days that may follow. For example, we can expect uncertainty. Due to the increased scale of mail-in voting, we may not know the winner of certain races, including the presidential race, on the night of — or even the days following the election. For many Americans, this may be surprising and unsettling. And this uncertainty may make us vulnerable to accidental misinformation and intentional disinformation. It is also possible that we will see a shift in voter share (from one party to another) as mail-in ballots are counted. Research suggests that in states where voters are given a choice, Democrats are opting to use mail-in ballots at higher rates while Republicans are opting to vote in-person on Election Day. This mirrors survey results that show that trust in mail-in voting is aligned with party affiliation. Depending upon when the mail-in ballots are counted, current totals could shift from red-leaning to blue-leaning (or, in some cases, vice versa). We have already seen information campaigns seeking to delegitimize those shifts — setting the stage for claims of “voter fraud.”

Here, we outline some of these scenarios and present examples of false narratives that we are likely to see during these different periods — a chaotic Election Day, an uncertain election night, and during a predicted “Blue Wave” (or alternatively a “Red Wave”) shift in ballot counts. We focus primarily on what we should expect to see in our information spaces, expanding upon what we have learned about how some of these narratives are seeded and spread by social media influencers, hyper-partisan media, political pundits, campaign representatives, and the U.S. president himself. We also provide some suggestions for how we (as members of the public and public communicators) might want to approach the emergence of certain misleading narratives, in terms of pre-bunking, debunking, or coveraging them as they spread.

Election Day: Sharing “Evidence”

Despite the record number of people who have voted early, Nov. 3 is still likely to be a chaotic day with countless stories of problems at the polls — some legitimate, but many fabricated.

There will likely be stories of voter suppression — including long lines that demotivate or prevent voters from casting their votes. There may also be cases of intimidation, with protesters congregating at polling locations. These protests could deter voting directly (e.g., people show up, but then go home without voting) or indirectly (e.g., people see images of these protests and decide not to go vote because they fear for their safety). States such as Alaska and Florida have already seen threatening emails. This will likely continue. Similarly, we may see accidental or intentional COVID-19 scares. Combined with long lines, these could further deter people from the polls.

As millions of people visit hundreds of thousands of voting locations, there are likely to be issues with ballots and voting machines. As there are in every election, there will be lost ballots, found ballots, people who voted but should not have, and people who should vote who are unable. We will hear of incidents where someone perceives that a ballot is being mistreated by a poll worker. People will complain about voting machines that aren’t working or aren’t properly recording votes. These concerns are not new; we saw similar concerns in 2016 and in previous elections. Some of these concerns will be legitimate, but it is important to remember these are rare instances relative to the vast majority of ballots and machines working properly.

As we grapple with the civic exercise of tens of millions of voters and votes, a crowd of self-deployed volunteers will be documenting and sharing their experiences — acting as unofficial poll observers and (perhaps unwittingly) gathering evidence that may be used by ongoing disinformation campaigns. On the Republican side, some of these efforts have been explicitly organized. President Trump and his surrogates have made repeated calls for an “army” of poll watchers to help collect evidence to support their claims of voter fraud. These volunteers, armed with mobile phones, cameras, and social media accounts, will generate terabytes of crowdsourced evidence to support claims of voter suppression and voting irregularities. Some will livestream to social networks, airing complaints and inciting audiences already primed to be concerned. The collection of evidence will be assembled, framed, and amplified by networks of social media influencers, hyper-partisan media, and political actors — to push false narratives that paint a picture of widespread voter fraud in order to cast doubt on the results of the election.

A Window into our Information Spaces on Election Day

All of this will result in a chaotic, emotionally-charged, and fast-moving information space. Social media users (and other news consumers) are primed for narratives of voter suppression, voter fraud, and other stories of voter disenfranchisement. Here, we describe some of the specific types of content, narratives, and propagation dynamics that we expect to see on social media and in our broader information ecosystem on Election Day.

Documenting voting experiences. We expect to see countless photos, videos, and other accounts of people participating in the voting process. These may include videos of people waiting in long lines to vote, images of confusing or erroneous ballots, and stories of malfunctioning voting machines. We might also see reports of people being unable to vote (e.g., due to a missing registration).

Initially, much of this content will be shared directly to social media by eyewitnesses. It will gain visibility as other users, including those with large audiences, amplify it. More strategic actors will reframe the content to align with existing political narratives. Photos and images will likely be taken out of context as they spread. First-person stories may become “copypasta” memes, as other users repeat the story or relate it as the account of a friend of a friend.

Some of this content will be framed as voter suppression, part of a sincere critique of our election processes, and in some cases building on well-established arguments of the disproportionate difficulties faced by minority and marginalized populations attempting to vote. Given the increased complexity of voting during the pandemic, we anticipate there will be an amplification of these images and critiques. These may be especially prevalent on the political left, particularly given the legal battles that have been waged over voting locations and mail-in deadlines. But we may see these same images and stories spread, opportunistically, on the political right as well — to reinforce narratives fostering doubt in the election results.

Concerns about voting during COVID-19. It’s possible that concerns about COVID-19 will be mobilized on Election Day, in some cases intentionally, to scare people away from the polls. We may see images — taken out of context, e.g., borrowed from previous elections — of people in crowded areas, not wearing masks, waiting to vote. There will likely be accurate accounts of extended lines and longer wait times as a result of social distancing, voters not wearing masks, and a lack of personal protective equipment for Election Day officials.

These images and stories could serve to demotivate people from going to the polls out of fear of catching COVID-19, especially in areas where cases are spiking. Though the original content may be shared by well-meaning individuals hoping to warn others of conditions at their polling places, these images and personal accounts may be strategically amplified — and taken out of context, e.g., said to be an image of a different polling location — to intentionally deter voters in specific races.

Concerns about intimidation and potential violence at the polls. We expect to see images and videos of protests, even armed individuals, accompanied by accusations of voter intimidation. Similar to the COVID-related voting concerns, these may sometimes be shared and spread sincerely, as well-meaning social media users attempt to warn others or draw attention to what they think is an outrage. But these could also be spread intentionally to try to frighten away potential voters. In some cases, the content could be borrowed from other events (not related to the election), previous elections, or even non-U.S. elections creating a false impression of safety concerns at the polls.

The protests, whether real or rumored, are likely to be associated with a range of different groups — for example Trump supporters, BlackLivesMatter activists, Antifa, or the Proud Boys. False rumors of protests from one group may catalyze real counter-protests by another.

Stories of mistreated ballots. We are likely to see photos, videos, and textual stories of purported mistreatment of ballots — by poll workers, postal workers, and other voters. Many of these reports will be accurate representations of problems at the polls. Others may be the result of misunderstandings by well-meaning, though perhaps politically motivated, volunteers. Some will be intentionally taken out of context, from past elections or other locations. As they move through the information space, from social media to partisan news media and back again, these accounts may be reframed in ways that exaggerate their impact and falsely assign political intent in order to reinforce an impression of massive and/or systematic issues.

Recommendations for Journalists: Covering Election Day Voting

One challenge will be how to cover suppression and/or intimidation stories in ways that don’t further the goals of those wishing to suppress/intimidate. For example, photos of long lines can discourage people from going to the polls. Contextualize visuals of long lines with descriptions of COVID-19 social distancing rules and draw attention (where possible) to good COVID-19 safety practices. Balance stories of long waits with more positive sentiments of voters exercising their constitutional rights.

Similarly, images of armed protesters near polling stations (or mere threats of armed protesters showing up) can deter voters. Considering the latter example, journalists should absolutely be covering cases where protesters are intimidating voters or threatening violence. However, it will be important to help viewers understand the scale and location of those problematic protests.

National journalists should stress that these cases are rare and be very specific about where they are occurring. Local journalists should assure voters in their areas that their polling places are safe and secure (when that’s true). Perhaps encouraging in-person voters to report positively (to journalists or through social media posts) on the safety and security of polling places could be a counter-weight to the crowdsourced armies of unofficial poll watchers.

Considering issues with ballots and voting machines, if journalists choose to highlight these stories, first, they should understand that by selecting them and making them salient, they may unintentionally be feeding false narratives of widespread voter fraud and fostering doubt in the election results. If they do choose to publish, they should ensure that these stories of voting issues appear in their proper context:

Mistakes happen in every election — ballots get lost, voting machines don’t work correctly.

Very rarely are mistakes due to intentional acts or systematic fraud.

Most mistakes have remedies (e.g. a person whose vote isn’t counted correctly can file a provisional ballot; many mail-in voters can track their ballots and request another if their ballot gets lost in transit).

A few lost or found ballots are not going to affect the outcome of most races. Be specific about the number of ballots and the expected margin in the race that they apply to.

Recommendations for the Public: Documenting Voting Day Experiences

For members of the public seeking to document their voting experiences, consider posting positive voting experiences. Negative experiences with voting receive much (and often warranted) public attention, but a focus on them can increase voter suppression. If you had a positive experience, share it.

If filming problems at the polls, particularly cases of intimidation or disenfranchisement, follow these tips from Witness.org:

Stay safe. Filming incidents can provoke violence. Consider whether it is safe to film, both for you and those you plan to film.

Provide a foundation for verification. Your video will be more useful if it can be verified by press, government agencies, and legal aid. If possible, turn on GPS tracking. Situate your film by showing local landmarks and street signs. Document who is filming by saying your name into the camera. Record continuous shots rather than shorter stitched together segments. If officials are involved, attempt to film identifying information.

Do no harm. Understand the potential risks to those you film. Obtain consent where appropriate. Be aware that filming, even when the intent is good, may scare away voters and balance what you document against that potential harm. Realize if your video goes viral those in the video may become targets in ways not anticipated.

Know the law. Know what you can and can’t film, and what legal rights you have as a filmer.

Election Night: Uncertainty, Exploited

The evening of November 3 will likely be an atypical election night — with wrinkles that many voters may not be expecting. Though millions of Americans will go to the polls that day and have their votes counted by machines that night, many others will have voted by mail and those votes will take longer to count. Even in states like Washington, which have had universal mail-in voting for several years, officials expect that it will take several days to count all of the ballots (which have to be postmarked by Election Day), and they have warned that high voter turn-out could lengthen the process. In states that have not used mail-in voting at this scale, the process could take even longer.

Voting experts note a difference between counting all the votes and making an accurate projection of the winner; it is possible to know the outcome of a race before every vote is counted. But noted changes to voting behaviors (e.g., massive amounts of early voting by Democrats) may require adjustment to existing projection models. Depending upon margins of victory, we may know some results right away. Others may take a week or even longer. All together, we are likely to experience a significant amount of uncertainty on election night and possibly days afterwards. This will build on the already high levels of uncertainty and anxiety surrounding this election.

Humans don’t like uncertainty. It makes us uncomfortable and anxious. We try to resolve it by finding new information and coming up with explanations. This “collective sensemaking” is increasingly enacted online. The process of collective sensemaking sometimes produces accurate explanations, but often results in rumors and misinformation. It can also be intentionally exploited, for example to spread disinformation. Election night uncertainty may present an opportunity (for those who choose to seize it) to sow more confusion about the process and more doubt in the results. Aligning with an existing campaign pushing misleading narratives of voter fraud, right-wing media and political pundits are likely to try to frame that uncertainty as illegitimacy. And voters on both sides of the political aisle may be vulnerable during this period to both domestic and foreign disinformation campaigns.

How Uncertainty (and Manipulation) Will Shape Our Information Spaces on Election Night and Beyond

Premature declarations of election outcomes. Similar to previous elections, media outlets, social media pundits and candidates will be competing to be the first to “call” election results. The anticipated delay in returns and the resulting uncertainty may create a vacuum that allows ill-intentioned actors (motivated by political or reputational goals) to fill the space with their own projections. We can expect to hear premature declarations of race outcomes spread across our information space, from political pundits (even the candidates themselves) out through social media spaces — and vice versa. This will be particularly prevalent around high-stakes races such as swing states in the presidential election and in a handful of key and hotly contested Senate seats, but we anticipate that premature declarations of victory may be made up and down the ballot.

Premature declarations will also come from media sources — both nonpartisan and partisan; mainstream and nontraditional. While we hope that traditional media outlets will refrain from calling election outcomes before accurate projections are available, we know that even forward-thinking projection models will be complicated by mail-in voting and so unintentional mistakes may be made.

Because projection models will likely produce results at a slower-than-normal rate, we also expect to hear premature victory calls from pollsters and “armchair data scientists” on social media. Twitter, for example, has been a hub for academic conversations on the proper way to adjust projections to account for the increase in mail-in voting. Many of these “experts” have built significant followings across platforms. We expect to see some of them make early election calls to promote the utility of their own projection models. There is a high likelihood of virality. Politically motivated actors will seize upon projections that favor their candidates and selectively amplify them to their audiences — through cable news, partisan media outlets, and social media spaces.

By drawing attention to favorable projections, partisan actors will work to “legitimize” a win for their candidate and possibly to lay the groundwork for contesting supposedly fraudulent election results. Premature and unauthorized declarations of election victories will increase public uncertainty when official declarations are released. In the interim, partisan actors will use this uncertainty to solidify claims about election fraud and rally their base to contest the legitimacy of the election.

Several social media platforms have already put in place policies to respond to candidates who claim victory publicly. In October, Facebook and Twitter released policy language that asserts labels will be applied to posts claiming victory before an “authoritative source” has called a race. These labels will: (1) inform readers that the race has not yet been called by election officials or national news outlets; and (2) direct them to the platform’s own official voting site for more information. However, labels do not disable candidates from prematurely claiming victory. As a result, we expect — and platforms seem to realize — that candidates’ victory claims will spread across platforms, especially using victory-related hashtags and images.

Fomenting confusion and distrust in election processes and results. Motivated by political agendas (foreign or domestic) or financial ones (attracting readers), there will likely be efforts during this period of uncertainty to sow confusion about election processes and doubt in the results. There may be specific attempts to frame the uncertainty as a sign of illegitimacy. These efforts will include calling attention to results that conflict with earlier polls, contradictory projections, and shifting margins between candidates. Even in non-political contexts, when “official” narratives change, people often interpret those changes as nefarious or otherwise purposeful manipulations. In this case, political influencers will be setting the stage for — and reinforcing — this kind of motivated reasoning within their base.

Building on existing narratives claiming voter fraud. These efforts to sow doubt and confusion in the results will also draw from and feed into other prominent narratives of voting irregularities and politically-motivated claims of systematic voter fraud. As mail-in ballots are counted, we anticipate efforts to resurface and highlight previous issues with mail-in voting, which may imbue distrust in the results from those ballots, especially in battleground states and local elections. On the political right, these stories will echo and reinforce messaging from a months-long strategy of delegitimizing election results, building an argument of widespread election fraud.

Mobilizing crowdsourced “evidence” from Election Day. We will also see the mobilization of “crowdsourced” content from Election Day (described in the section on Election Day, above) — including photos of long lines and intimidating protesters, videos of perceived irregularities in and around the voting booth, and first hand accounts of prospective voters who were not permitted to vote. After the polls close, as we wait for results and concessions, this content will be selectively amplified and woven together by online crowds and media outlets to provide support for existing meta-narratives of voter fraud (on the right) and voter suppression (on the left). It is possible that these narratives will resonate, within a confusing and uncertain information space, with more general feelings of election illegitimacy. Studies of human behavior during times of crisis — also characterized by uncertainty and anxiety — suggest that people will be susceptible to rumor, misinformation, and manipulation during this time.

Fomenting feelings of disenfranchisement. We are likely to witness sincere expressions of disappointment, anger, and outrage by people who were denied the ability to vote or people sympathizing with others who were denied their vote — either at the polls or through their mail-in votes. For example, we are already seeing significant numbers of ballots being denied because of mismatched signatures. Depending upon the laws in a particular state (which have been changing up until the final moments of this election), some ballots may not be counted if they arrive late — which opens up the possibility that issues with the U.S. Postal Service will lead to uncounted votes. The stage has already been set for these kinds of stories, and similar accounts of voter suppression, to arise in the aftermath of the election. Again, we will see photos and videos and textual accounts spreading via social media. These may elicit strong emotional responses, from people on both sides of the political spectrum.

Though they may initially be shared by well-meaning people attempting to draw attention to real issues of voter suppression, politically-motivated actors may choose to amplify these stories — with the goal of fomenting feelings of disenfranchisement. We may see “copypasta” type campaigns, where the same story of disenfranchisement is repeated (word-for-word, with slight variations, or as “friend of a friend” reports) by dozens or even thousands of different accounts, posted to social media (often as replies to high follower accounts) or added as comments to news articles. We will likely see hyper-partisan media, clickbait websites, and state-controlled propaganda outlets aggregate and highlight these stories of disenfranchisement. This is a likely strategy for foreign actors from non-democratic governments, who will seize the opportunity to highlight failures in the democratic process. Domestic actors may also amplify these stories, especially prior to a concession from one candidate or another, to build popular support for an effort to legally contest the results.

Accusing social media platforms of censorship and bias. Over the last several months, the social media platforms have been updating their policies and applying them in new ways — including adding labels and limiting the virality of election-related misinformation. They are likely to continue these actions and even apply new mechanisms for dampening the spread of problematic information on the night of — and possibly for days after — the election. And for those affected by these actions, there is likely to be anger directed at the technology companies, including claims of censorship and political bias. We expect to see efforts, by political leaders and self-deployed social media users alike, to pressure the companies to change their policies and undo their actions. Some of these may be coordinated, with political leaders, partisan media pundits, and social media influencers converging around a particular message and reinforcing it across their audiences.

Recommendations for Journalists: Covering Election Uncertainty

One opportunity for journalists — and one that many are already taking — is to help prepare their audiences for the potential uncertainty of election night and beyond. Setting expectations and helping people to understand why the results aren’t yet available can help to reduce the anxiety that often accompanies uncertainty and helps power the rumor mill.

Looking ahead to how the uncertainty may be exploited for political gain (by both foreign and domestic actors), journalists and other communicators may want to stress that uncertainty does not mean illegitimacy. It will be valuable to stress that the uncertainty is actually expected in this case, that we likely won’t know the results right away, and that leading candidates may change as additional votes are counted.

Journalists should be careful not to amplify cases where political pundits or partisan media have “called” the election prematurely. These predictions may be well-intentioned, designed to sow confusion, or purposefully laying the groundwork for later rejection of contrary results. In any case, it is likely better to wait for the experts to weigh in and avoid amplifying these potentially misleading calls. To avoid potential manipulation, as we wait for clarity in the outcome, journalists may want to avoid filling the gap with social media chatter.

What journalists can do during this time is to alleviate anxiety by helping the public understand when the uncertainty might resolve. For example, explain to readers what threshold must be passed for a winner to be called in whatever race you are covering. Be explicit about expectations of when this could occur.

As news of voting issues and irregularities from Election Day percolate through social media, journalists may want to reflect on how highlighting particular stories may create a false impression of widespread irregularities and resonate with false narratives of systematic voter fraud. One potential remedy is to balance coverage of problems with coverage of successful voting experiences. Report where the voting process is going well, and report the number of votes that have been validated. Try to provide context for the lost ballots and voting machine mishaps, for example by drawing attention to the total number of votes being processed and the current margins.

Post-Election Day: Decontextualized Irregularities, Delegitimized Shifts

As a result of COVID-19 and changes in how individuals intend to vote in 2020, many analysts predict that a “blue shift” may take place in some states, which means that the Democratic share (or proportion) of the vote might increase substantially between early counts and final ballot totals. Others have hypothesized such effects may be more minimal, or even reversed in other states.

Shifts in the makeup of an overall vote count are not unique to this election. In recent elections, both Senate and House races have swung from one candidate to another following post-Election Day ballot counting. Although previous shifts have in the past favored candidates on both sides of the political spectrum, analysts expect that a shift in the upcoming election will favor Democratic candidates in many states due largely to a widespread increase in mail-in voting. Perceptions of late-stage changes are likely to incite confusion and exacerbate claims of fraud, as they did in 2018.

While the mechanisms of this predicted shift are known in advance, there will be efforts to portray the shift as something more sinister. On the right we expect the leveraging of two interlocking narratives. First, a false but largely non-conspiratorial narrative that individual fraud with mail-in votes is responsible for any shift. Second, a set of false, conspiratorial claims of “ballot-stuffing” that assert that any shift is the result of a systematic, coordinated effort of local authorities to alter the election night vote through the addition of forged ballots or the swapping of “real” ballots for fake ones.

A voting shift is not currently perceived as a threat by most Democrats. However if votes do begin to shift from blue to red, and if those changes are unexpected (for example, because they run counter to previous polling), we may see skepticism and even resistance on the left. We have already seen a prominent Democrat (Hillary Clinton) encourage Joe Biden to not concede, “under any circumstance.” In the event of a red shift, it is likely that political influencers will use their platforms — on social media and in the press — to question the results. The resistance narratives that arise may focus on historically distrusted entities such as voting machine manufacturers and other corporate entities involved with the processing of votes. If reports of foreign hacking or other interference emerge, which they are likely to, these may also be used as rationale for contesting the election results.

How Our Information Spaces Will Be Shaped to Fit Narratives of Election Delegitimization

Many of the concerns we expect in the week or weeks after the election are legitimate concerns. Were voters intimidated? Were ballots mishandled or discarded? Is there statistical evidence of error, fraud, or disenfranchisement? These questions will take time to answer. In the interim, disinformers will seed alternate explanations.

We expect to see doubts about election processes exploited to further existing (false) meta-narratives of massive voter fraud and to question potential shifts from one party (or one candidate) to another. Depending upon margins of victory, it is possible that these will come together to provide public justifications for legal efforts to contest the results of the election.

Assembling the “evidence” to fit the narrative delegitimization. As we described above, it is likely that a large number of unofficial poll observers and other voters will document and publicly share their experiences at the polls on the day of the election. In addition, there is and will continue to be a parallel stream of stories originating in social media and local news outlets, documenting issues with mail-in ballots. These stores of digital “evidence” of election issues will be cherry-picked and assembled — by politically motivated actors — to fit narratives that seek to undermine trust in results that favor the oppositional party and delegitmize shifts from a favored party or candidate to a disfavored one.

We imagine this process will be collaborative and participatory. In some places, it will be bottom-up, with politically-motivated social media users working to collectively curate and frame content to fit prevailing narratives and frames (e.g., voter fraud). In other cases, it may be more top-down, with partisan media outlets pulling together disparate data points and providing new strategic narratives. Relying upon new material from voting day, this process will be emergent and messy. But as the days progress, we imagine that the information space may grow less chaotic, as media and other influencers begin to home in on a few specific stories or narratives — the ones that appear to have the most “legs” in the information space. And though it is difficult to know exactly which stories will resonate the most, examples from previous elections may provide some insight.

For example, we expect to see some of the following “evidence” surface to challenge an unwanted shift in party proportion:

Videos or photographs of boxes of ballots being moved, or left unattended.

Videos or reports of broken election machines misrecording votes.

Theories about actions poll workers supposedly used to identify and eliminate or alter ballots based on party (see, for example, the debunked ballot markings theory).

Accounts of altercations with poll workers.

Videos claiming to show issues around ballot dropboxes, such as voters dropping off more votes than allowed, or security being mishandled.

Video, photos, or verbal accounts claiming to show election staff/officials altering or mishandling ballots during the counting, canvassing, or signature verification process.

Though much of this evidence will derive from “real” (though misframed) events, we should also expect to see explicitly fake and deceptive images and video, for example, allegations of U.S. election fraud which actually depicted events in Russia.

Ballots discovered, ballots lost. Stories of ballots lost and ballots found are likely to be some of the more robust and repeated stories in the days after the election. Elections are events that happen once every couple of years, often staffed by a mixture of volunteers and temporary workers. As with anything done only occasionally, errors are likely to happen, especially when workers have to navigate a complex set of laws and procedures. And the likelihood is that some ballots that were supposed to go to location A actually end up in location B. This may be particularly true for ballots that have been set aside in the weeks before the election to be counted on Election Day (such as absentee ballots), or set aside to be counted last (such as provisional ballots).

On the political left, these stories may play into conspiracy theories around the suppression of mail-in votes, known to be more Democratic.

On the right, we expect such events to play into more complex and conspiratorial narratives around institutional ballot-stuffing. For the right, found ballots from likely Republican voters will be seen as ballots which partisan officials had attempted to discard or hide. Conversely, right-wing conspiracy theorists will frame likely Democratic ballots that are found as institutionally “forged” ballots that are being added after the election to fix the results.

Stories of this type have a high potential for virality as they will emerge daily after the election, and rely on a single narrative that has been widespread in online right-wing culture since the 2016 election’s debunked warehouse of ballots story. Narratives that plug into a steady stream of predictable but easily reframed events can be quite robust and participatory (see a parallel trend in narratives around “mail-dumping”).

Inversion of the protection narrative. As mentioned, the major protection against absentee voter fraud — and by extension duplicate votes in error — is that instances of fraud are highly likely to be caught, and subsequently severely punished. One approach to creating a false appearance of fraud in a system largely free of it is to flip this protection narrative on its head. When protections are triggered, e.g., when someone is caught submitting multiple ballots, instead of portraying that as an example of how elections are protected, those seeking to sow distrust in results may portray that as an example of how elections are vulnerable. It’s as if you took a list of all the failed attempts to rob a bank and portrayed them as evidence of the bank’s lack of security.

We’ve seen examples of this already:

Groups promoting “election security” have often used the number of mail-in ballots rejected as proof of the level of voter fraud in mail-in ballots. In reality, very few rejections are a result of detecting voter fraud, but rather the application of stringent checks, which may result in a significant amount of voter disenfranchisement this year due to higher rates of mail-in voting.

Individual events have also been popularized. One particularly viral story was of a Florida man who requested a ballot for his dead wife. The signature match failed and a lookup showed his wife as deceased and he was arrested. The protections worked. Yet the surrounding discourse most often claimed this showed an election vulnerability, not evidence of the security of the system. In this case, the incident took on a political and racial element. As news of it spread through right-wing media, the fact the perpetrator was Black and a “self-described” Democrat was highlighted, but the fact that he was a Trump supporter (trying to test rumored vulnerabilities in the system) was minimized.

Bad Statistics. Another type of narrative used to support the meta-narrative of massive voter fraud will not be based so much around events — e.g., ballots rejected, voter fraud identified — but around dodgy statistical analysis. Often these statistics will emerge from statistically naive calculations that either intentionally or unintentionally compare unlike things. A good example is the deceptive claim that Los Angeles County has more registered voters than eligible voters, a statistic that relies on deceptively comparing both active and inactive voters to eligible voters (inactive voters are inactive for a reason). Other bad statistical treatments have framed uncast ballots as missing. We should expect variations on this technique after the election, purporting to show “excess votes” (i.e. fraud) based on raw totals and similar statistical manipulations.

Allegations of foreign hacking. As the election nears, we are increasingly hearing about foreign interference. Related to these efforts, another possible narrative — one that could take root on the political left or the right — involves allegations of election hacking by foreign operatives. These allegations are easily made, but will take far longer than an election week or two to prove. If such events are believed to have occurred, expect to see (as in 2016) confusion around differences between intrusion capabilities and actual actions that may have altered vote totals or changed what votes were accepted. In other words, regardless of how effective these hacks may have been at actually changing votes or affecting outcomes, they can and likely will be leveraged to undermine the perceptions of election integrity (which may be their primary purpose).

Recommendations for Journalists: Covering Shifts in the Vote Count

As mentioned earlier, as we shift into the week after the election a prominent source of misinformation is likely to be falsely framed local reports of irregularities, spun out to confirm more national narratives about the legitimacy of the election — and especially narratives that seek to throw doubt on shifting vote shares. Reporters can reduce the impact of this misinformation through “day one” framing of stories about irregularities.

Here are some tips on covering such stories in the days after the election.

Citizens hearing a variety of explanations around voting shifts and patterns can come to believe that things are mysterious or in contention, when in fact they are well-understood and explainable (e.g., why mail-in ballots may shift vote shares towards Democrats). Emphasize the expert narrative, and, as importantly, make the scope of consensus clear. Try to express the level of expert agreement on issues of fraud and shifting totals as precisely as possible.

Conspiracies about voting irregularities or disturbing video will thrive in the space between questions and answers. Journalists can avoid exacerbating conspiracy theories by providing likely explanations in initial reporting. Seek professional or expert insight even in initial reports, and let the audience know the most likely explanations for odd or confusing events.

Stories about ballot mishandling, ballot-stuffing, and forged ballots are likely to be variations on old stories. Prepare your newsroom by reviewing spurious claims from previous elections. Scanning articles like BuzzFeed News’s 2018 misinfo roundup can prepare reporters for claims they are likely to see.

Finally, you may not know how a specific story will turn out over time, but you can let your audience know how similar allegations have played out in the past. As an example, a video of a poll worker “altering” a ballot may require more investigation, but you can point out whether similar incidents in the past have proved to be due to malicious intent, misunderstandings, or fabricated incidents.

In all these cases, the key is to be prepared to provide context as incidents are reported. What do experts think? What are the most likely explanations? How have similar claims panned out in the past? By having such context in initial reporting (and making sure such context is reflected in your headlines and social media excerpts) you can better inform the public and make it less likely your story will be used as part of a broader delegitimization campaign.

Looking Forward

Our democratic institutions are under a great deal of stress. As we head towards a tumultuous election day — and perhaps several contentious post-election weeks — many of us worry about the integrity of our vote, and the health of our democracy. Clearly, our society has a great deal of work to do to build trust in our election processes, to make them stronger and more fair, to eliminate systematic voter suppression, and to prevent actual fraud (even a few cases are a few cases too many).

Productive criticism is designed to make something stronger. But another kind of criticism — the kind that we are encountering repeatedly in this election cycle — is meant only to break things down. Certain political actors seek to exploit the weaknesses in our voting and information systems, sowing doubt in our processes to advance their own political objectives. These manipulations destabilize the foundations of our democracy — causing us to lose trust in our democratic processes, our information providers, and ultimately, each other. Our hope is that by better understanding these dynamics and identifying ways to counter them, we can become more resistant to manipulation and consequently stronger as a society.