Confusion Over Election Technology Contributes to Rumors and False Claims

Stories about breaches of election technology present challenges to readers, who process information about breaches through the lens of electoral impact, often without sufficient context.

In this post, the Election Integrity Partnership examines the discourse associated with a recent incident in Kent County, Michigan, in which a poll worker was arrested for allegedly tampering with an electronic poll book. While the technology breached has no connection to election results, online the breach was interpreted as an instance of election fraud or cheating.

Evidence from preliminary analyses highlight areas for improvement among journalistic outlets in the presentation of specific election technologies in future news stories, as well as implications for misinformation analysts.

Photo above: The Gaines Charter Township Offices near Grand Rapids, Michigan, in Kent County. (Photo by the Election Integrity Partnership)

This Election Integrity Partnership analysis was co-authored by Mike Caulfield, Morgan Wack, Emma Spiro, Kristen Engel, and Sydney DeMets (University of Washington Center for an Informed Public). This post was updated on October 25 to add more precision in description of electronic poll books.

Introduction

The advent and integration of technology in elections has improved the security of the voting process. However, these technologies have also served as a prominent target for false narratives of election fraud and conspiracy theories.

Not all efforts to disrupt the voting process are imagined, with recent incidents including the arrest of a Republican poll worker in Kent County, Michigan, who is alleged to have plugged a USB stick into a computer in order to gain access to its electronic poll book (which contained a list of the district’s registered voters along with their addresses). Incidents with a similar focus on election technology have been used to stoke distrust in election technologies more broadly despite the specific technologies in these incidents having no direct effect on the election results.

Using the recent case in Kent County as an illustrative example, the Election Integrity Partnership seeks to dispel common misconceptions about the voting election technologies and equipment currently in use in U.S. elections by detailing the important distinction between non-voting election technology and voting election technology. In addition, the case demonstrates how failures to distinguish between specific technologies can lead to inaccurate assessments regarding the potential impact of breaches or other systemic vulnerabilities.

While the distinction laid out here uses a recent incident in Michigan, the analysis is applicable to a wide variety of confusions that emerge online after breaches, errors, and malfeasance around election technology unrelated to voting. This was also relevant in the response to the recent Konnech allegations, where the CEO and founder Eugene Yu’s arrest was linked on social media to issues of election integrity despite the arrest having been focused on potential access to poll workers’ personal information.

Varieties of election technology and related confusions

The election process comprises multiple systems and procedures, from registration, to voting, to tabulation, reporting, and certification. Many of these processes are technologically mediated. Some technologies are visible to the voter — for instance, the tabulator they put their ballot into or the state website through which they track their vote. Others are invisible, such as barcode tracking systems for inventory, poll worker management software, or even email systems used by election staff. Importantly, some systems (e.g., tabulators) are involved in the process of voting or counting votes, whereas others (e.g., electronic poll books) play a supporting role, and breaches of supporting technologies cannot directly affect votes or results. [1]

Despite this crucial difference, as the National Conference of State Legislatures notes, “when most people think of election technology, they think of the equipment used to cast and tabulate votes.” This produces a challenge: how can communicators — whether election officials, press, or concerned citizens — effectively disseminate information about breaches of election technology not involved in voting or tabulation, in a way that conveys the seriousness of such breaches while not giving readers the impression that potential impacts include the alteration of results?

In our analysis, we explored news reports and audience reactions on Twitter surrounding a breach of an electronic poll book in Michigan and subsequent arrest of the poll worker. The conversation we observed had confusion and false connections to voter fraud from both U.S. Right and U.S. Left perspectives. We found that:

Less precise and potentially misleading terms around the technology were more shared than precise terms with the top three shared posts describing the electronic poll book as either “voting equipment,” or a “poll machine.”

Public reactions to the top most shared posts demonstrate misperception of impact of the incident on election outcomes, suggesting that while careful language is always advised, the public may benefit from education on the various roles of election technology.

Incident background

On September 28, 2022, a Republican election worker was charged with two felony offenses for allegedly having tampered with an electronic poll book in Gaines Township, Michigan, near Grand Rapids in Kent County. Electronic poll books are electronic versions of familiar paper records, and are used to process voters and generate precinct records. They may contain information such as the voter’s home address, their party preference, as well as procedural information used when voters are processed at the polls, such as whether a mail-in ballot has been issued, and their home precinct or ward. They are not typically connected to voting equipment, and contain no record of how people voted other than publicly available registration data.

The worker was alleged to have inserted a USB drive into an electronic poll book after voting had completed in the August 2 primary election. On October 7, Kent County Clerk Lisa Posthumus Lyons confirmed the incident did not affect the outcome of the election.

This incident was reported on by several media sources such as NBC News and Fox News and discussed on social media platforms including Gab, Gettr, Reddit, Telegram, and Truth Social. We observed this spread at the EIP. Below is a temporal graph of the approximately 18,600 tweets in our data that occur between September 22 and October 7 that referenced either the accused by name or by position as a Michigan poll/election worker, the unauthorized device, terms referring to a USB device in Kent County, or the event, tampering in Michigan or Kent. As this visualization of the data shows, the conversation around this incident spiked briefly on September 29, before dying down.

Our analysis of the Twitter conversation around the incident revealed that social media commenters did not correctly characterize the nature of the violation and its potential impact. Instead, much of the surrounding conversation and reactions to this story wrongly suggested that accessing the poll book could be a method of cheating in the election, or was evidence of widespread fraud in previous elections.

Findings

To investigate the role of election terminology and associated confusions we focus our analysis on the top five tweets that received the most retweets. These five tweets received an order of magnitude more engagements than others related to this incident. These five tweets are seen in Table 1 below.

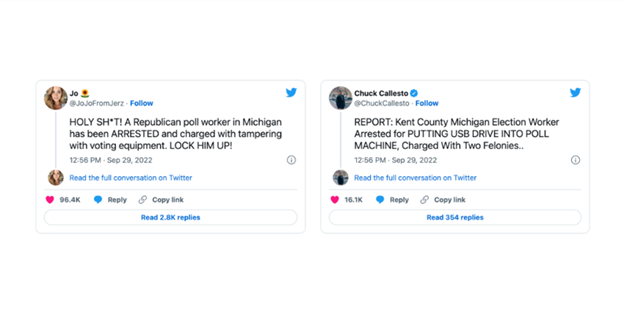

The top two tweets, seen below, illustrate how election technology is referred to in a variety of ways, with one tweet noting charges of “tampering with voting equipment” and the other “poll machine.” Some other top retweeted tweets use the terms “electronic poll book.”

These top two tweets also differ in their specificity of the accused poll worker, where one explicitly calls attention to the fact that they were a Republican and other does not. This trend extended to the other tweets in the top five retweeted, the tweets from left-leaning users and organizations emphasizing the partisanship of the poll worker. Specifically, two of the top five were left-leaning organizations that both began their Tweet with “A Republican poll worker…”, reflecting this trend.

Table 1: Top five most retweeted posts on the arrest of a Republican poll worker in Kent County, Michigan.

To explore the public reactions and conversations in response to this story we collected all replies to the top five retweeted posts in Table 1 (a dataset of 8,113 replies across the five tweets). We then look at the common words and phrases in these replies. When examining the replies with respect to the election technology named, the terms “voter fraud” and “election fraud” were amongst the top three two-word phrases (bigrams). In Table 2 below we show the number of replies and frequency of these phrases across the set.

Table 2: Frequency of terms “voter fraud” and “election fraud” in replies to top retweeted tweets.

Election and voter fraud involve attempts to manipulate results, whether as a voter, election worker, or outside party. As noted, the incident in question could not have impacted the results of any election, and would not commonly be referred to by these terms. However, as demonstrated in the replies shown below (direct responses to the highly shared tweets in Table 1), social media users connected this incident to various stories around blaming Republicans, claims of fraud, and general confusions, along with distrust, of election technology. [Note: the text of these has been modified to protect the identity of the posters.]

Blaming Republicans:

“All these accusations of voter fraud but they're the ones that keep getting caught.”

Ties to fraud more generally:

“I thought you said there was no voter fraud.”

“DEMAND HAND MARKED PAPER BALLOTS! RANDOM AUDITS! RECOUNT BY HAND!

NOBODY FROM EITHER POLITICAL PARTY TRUSTS THE MACHINES. MYSELF INCLUDED.”

Discussion of the technology:

“I thought that voting machines couldn't be tampered with or was that only for the 2020 election?”

“It wasn't a voting machine. An old man plugged in a USB drive into a computer that was not used for voting. Details matter. They don't say, but I wouldn't be surprised if he was just charging his phone, and thought it would be okay, since it wasn't a voting machine.”

Conclusion

To understand the impact of vulnerabilities in election technology, citizens must be informed of distinctions between various forms of such technology. Crucially, a distinction must be made between vulnerabilities that impact voting election technologies and non-voting election technologies. This is not to say that failures in surrounding technologies cannot impact elections — failures in electronic poll books, for example, could cause delays at voting locations that could dissuade some voters from voting. Breaches of poll worker data could lead to harassment of poll workers, adversely affecting their ability to do their jobs.

That said, voting and tabulation equipment represent a special class of election technology, with a special class of risks, and when citizens conflate this more specialized class with broader technologies they form incorrect perceptions of electoral integrity and legitimacy. Given our research we suggest the following.

For election communicators and press

Embrace specificity: Communication about election processes will always be read by the public with an eye, first and foremost, as to whether the new information warrants decreased faith in election results. When it comes to technology, the answer to that question is almost always “no” — either because the system is not a voting or aggregation system or because various checks and balances exist to catch and correct technological errors.

Where equipment is unrelated to casting votes or the tabulation and reporting of results we encourage those discussing it to make that clear, and provide that information early in the process. We caution against the use of overly general terminology, as occurs when outlets reference all election-related technology as “voting equipment.” As an alternative, communicators should work to provide their readers, viewers, and listeners with context regarding the specific technology being referred to in the story,and use language that distinguishes technology that impacts different parts of the election process. While we do not have specific recommendations for language here we would suggest at minimum distinguishing between:

Technology that helps process voters (e.g., registration systems, electronic poll books, geographical information systems).

Technology that records or processes votes (e.g., tabulators, electronic voting machines).

Technology that provides online public insight into the process (e.g., “check my ballot” websites, preliminary reporting systems, ballot image posting sites).

Technology that plays a supporting role in the election process (e.g., election worker management systems, mail-in ballot processing systems).

Reiterate the pillars of election integrity. As always, we advise reiterating the crucial features that provide for the accuracy and security of the U.S. election system. First, the process is transparent. Second, the process has bipartisan oversight. Third, the process is run by professionals who apply election best practices that have been developed over time to keep elections secure. Tying individual communications back to these larger ideas helps build future resilience.

Create explainers ahead of time: When these sorts of stories initially break, there is a gap between when confusion first develops around the story and when a specific fact-check emerges. However, the general confusions that emerge are relatively predictable. To address this gap we encourage press and election officials to produce explainers ahead of time that detail the different types of equipment and software in the election process. What does an election worker management system do? What doesn’t it do? What about electronic poll books? Creating explainers ahead of time is part of a “help the helpers” strategy: when initial sensemaking happens around an event, providing those truly looking to make sense of the situation with tools to educate others can raise the quality of the conversation, especially during the early phase.

Check headlines and preview text for clarity: In the most common URLs circulating on Twitter in association with this incident, too often crucial details regarding the true and potential impact of breaches were not contextualized for readers. As research shows that few readers, particularly those likely to share the story on social media platforms, actually read the underlying content these headlines should properly frame the associated risks. We encourage publishers to look at both headlines and the associated preview cards, asking whether a reader reading only these elements would form an accurate perception of the potential impact of the event described.

For researchers

This case also serves to highlight the difficulties of quantifying reactions on social media at scale. Language is nuanced. Simple, rapid analysis of key terms and phrases presents a limited view of the public interpretations and conversations about topics online. Though these analyses can provide examples and evidence of certain phenomena they can also lead to misinterpretations of the data, for example where top words and phrases are not properly contextualized to account for differences between corrections and amplifications. The complexities of election technology that aided in the confusion and misinterpretations seen in some of the replies above pose challenges for researchers. As with communicators, researchers should remain hesitant to draw firm conclusions from preliminary analyses reliant on textual analyses of social media data, particularly when text is terse and short.

Notes

[1] As is often the case with U.S. elections, blanket statements are difficult to make. Some older electronic poll books (EPB) provided codes to unlock voting machines and needed to be connected to voting equipment to do that. Additionally, while EPBs do not record votes, in many states they do store information about which primary someone voted in. This is public information after the election. In Michigan, access to the internet is used to download EPB updates but is disabled on election day.